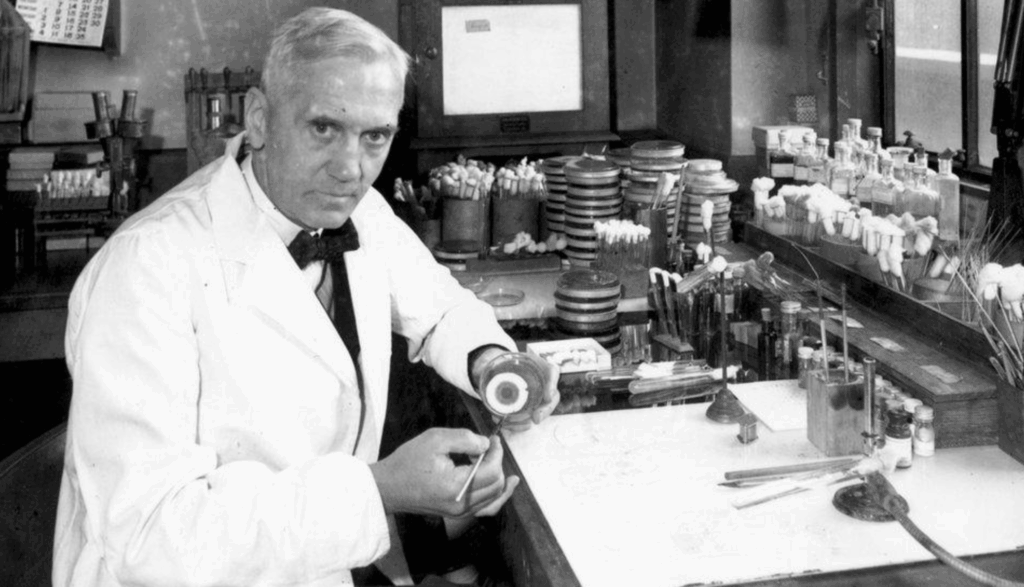

On a September day in 1928, history changed forever in a quiet laboratory at St. Mary’s Hospital, London. The Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming, returning from a holiday, found something peculiar on a Petri dish he’d left unattended – a patch of mold surrounded by bacteria-free “clear zones”. This unassuming dish would become the birthplace of the antibiotic era.

Alexander Fleming and the Dawn of Antibiotics

Back then, the treatment of bacterial infections relied largely on luck and limited remedies. Countless lives were lost to simple cuts that turned septic. Fleming’s sharp eye noticed that this mold – later identified as Penicillium notatum – was producing a substance potent enough to kill a wide range of harmful bacteria. He called this substance “penicillin.”

The importance of Fleming’s discovery was not immediately recognized. Attempts to extract pure penicillin proved difficult due to its instability, and Fleming’s 1929 publication barely hinted at its revolutionary medical potential. Only years later, as World War II raged and bacterial infections threatened wounded soldiers, did a team led by Howard Florey and Ernst Chain at Oxford University turn Fleming’s laboratory curiosity into a life-saving drug.

Penicillin’s arrival rewrote the rules of medicine. Suddenly, previously deadly diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, and rheumatic fever could be swiftly defeated. It is no exaggeration to state that the discovery of penicillin ushered in the modern era of antibiotics – transforming scientific theory into the hope of healing for millions.

As Fleming himself later reflected:

“When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.”